‘The heavy brass trellis which then screened off these galleries, and their bad ventilation, made them quite unnecessarily tiring and even exhausting,’ Millicent Fawcett, writing in 1924.[1]

The grilles deliberately screened the Ladies’ Gallery unglazed windows, partly to place women formally outside the House of Commons chamber, partly for fear of distracting the men who would otherwise have been able to see women watching them at work. Millicent Fawcett, leader of the suffragist organisation the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), complained that having to peer through the grilles made the Ladies Gallery ‘a grand place for getting headaches,’[2] and in the early 20th century they became a target for suffragette militancy.

‘We do not wish to attach undue importance to so purely domestic a proposal, nor to attribute to any serious principle a custom which is merely a survival of a more picturesque age; but we beg you to remember, in your deliberations, that it is a very uncomfortable thing to have to sit in a gallery from which little can be heard and still less seen. We feel this the more acutely because we are assured that the interest of these Debates, which we cannot hear, far surpasses that of any other legislative assembly in the civilized world.’[3]

Their tactic was to get support from women representing a wide variety of respectable and influential organisations, titled women and women related to MPs and peers, and women with impressive qualifications and jobs. Correspondence on the petition includes some amusing comments such as this one from Dr Jane Walker (who did sign):

‘Really men require so much patting on the head when they do anything for us! I feel it is an absurdity to petition them to do anything so trivial. We shall see that they do it when the Vote comes.’ Jane Walker, LRCPS Physician New Hospital for Women, 12 May 1917.[4]

Although most women approached signed without hesitation, a few did refuse. One such was Gertrude Gow of the League of Honour for Women and Girls of the British Empire, who wrote, ‘I much prefer sitting behind the grill, than I should do if it were taken away!…I hope however you will get your desire, as you are many and I should imagine I am alone.’[5]

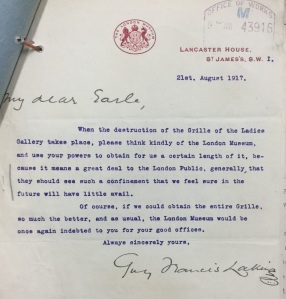

The Representation of the People Bill passed another hurdle in June, when clause 4 (votes for women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications) cleared committee stage in the Commons. Two months later, the House of Commons finally voted on the removal of the grilles – although you would not easily guess it from the Parliamentary Debates. On 15 August 1917, Reginald Blair MP asked the First Commissioner of Works if he would give the estimated cost and number of men expected to be employed on the removal of the grille. (Blair was an anti-suffrage Conservative MP who had even made his maiden speech against suffrage, when he had been elected over the great suffrage supporter George Lansbury back in 1913). Mond replied ‘The estimated cost is £5 and the work should require an average of two men of various trades for three or four days.’[7]

I went over to the Houses to see where it would be possible to utilize in a dignified manner the grille taken down from the ladies Gallery, and I submit the following proposal for the approval of the First Commissioner. It is my opinion the best suggestion that can be made, and will retain in the Houses of parliament the whole of the grilles in service where they can be readily seen by the public and any interested party. The proposal is to fix the grilles in the windows of the various Lobbies which open on to the Central hall. The grilles will fit the positions excellently...[11]

This was agreed, and so most of the grilles came to be placed in Central Hall, which today we call Central Lobby. Any visitor to Parliament today can admire them there. There is a small plaque by the Admissions Order Lobby that records what they are.

If you’re visiting Parliament today, do look out for the grilles in Central Lobby and remember their story!

Mari Takayanagi

With thanks to Elizabeth Hallam-Smith and Robin Fell for the research for this blogpost

More on the grille on Living Heritage

[1] Millicent Garrett Fawcett, What I Remember

[2] Millicent Garrett Fawcett, The Women’s Victory – and After

[3] The National Archives, WORK 11/227

[4] LSE Women’s Library, 2LSW/E/03/7

[5] LSE Women’s Library, 2LSW/E/03/7

[6] LSE Women’s Library, 2LSW/E/03/7

[7] HC Debates, 15 August 1917, col 1168

[8] HC Debates, 15 August 1917, cols 1190-1191

[9] The National Archives, WORK 11/227

[10] Millicent Garrett Fawcett, The Women’s Victory – and After

[11] The National Archives, WORK 11/227

I enjoy getting these posts. I see you have some guest posts also. Can you tell me who to contact re this as I may have something

Paula Keaveney

________________________________

LikeLike

Hi Paula – do email us vote100@parliament.uk

Best Melanie

LikeLike