Guest post by the Hansard Writing Team

On 9 March 1954, four MPs put aside party political differences to present an 80,000-signature petition to Parliament demanding equal pay. Ulster Unionist Patricia Ford, Conservative Irene Ward and Labour MPs Edith Summerskill and Barbara Castle grabbed the attention of the press by arriving at Westminster with the petition on 8 March in horse-drawn carriages decorated in rosettes and streamers in suffragette green and white. Nothing was overlooked in planning this photo-opportunity: even their coachman, Dave Jacobs, was a veteran of feminist campaigns, having driven for Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett.

The Chancellor’s distressing statement

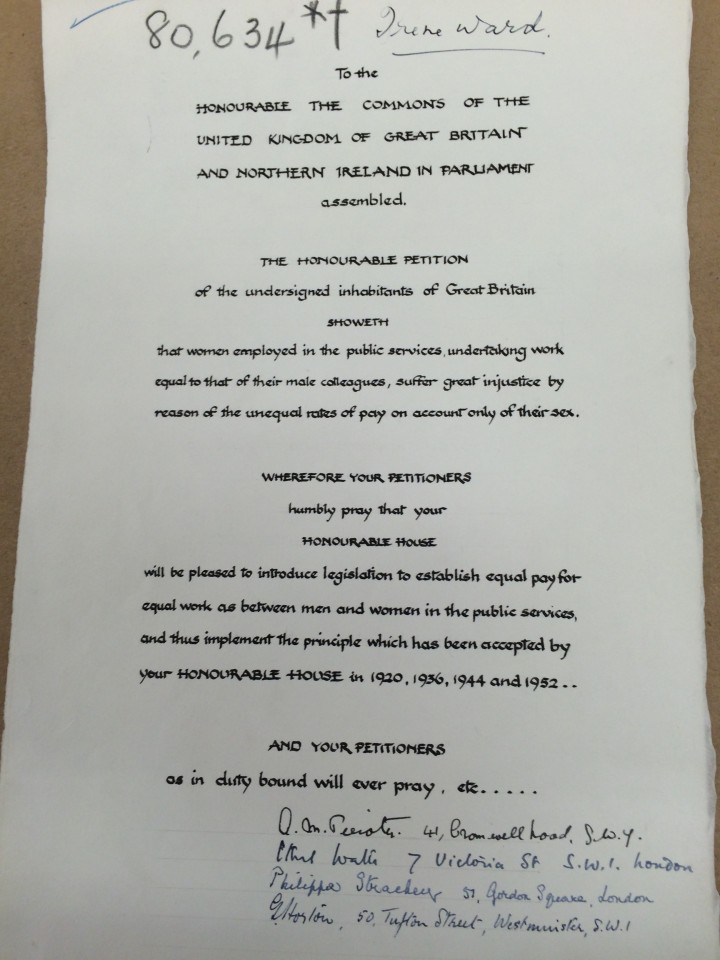

The petition was instigated by the Equal Pay Campaign Committee (EPCC), which was set up during the second world war to close the huge pay gap between men and women in the public sector in accordance with the principle accepted by the House of Commons in 1920, 1936, 1944 and 1952.

In 1951, Labour Chancellor Hugh Gaitskell said in the Chamber that equal pay would drive up prices and increase demands on public spending. EPCC Secretary Gertrude Horton said that that was a “distressing statement” and fired off letters to sympathetic MPs asking for suggestions for parliamentary action on equal pay. Her mailing list included Irene Ward, Barbara Castle and Liberal politician Jo Grimond. On 2 August, Ward said in Parliament that Gaitskell’s “unfair and inaccurate” claims had “caused great resentment and bitterness” among public servants and trade unionists. She called the Chancellor “a little dictator” for blocking a move to pay Hansard reporter Jean Winder the same as her male colleagues.

In 1952, with the Conservatives now in power, the Commons passed with a resounding majority a motion by Labour MP Charles Pannell calling on the Government to announce “an early and definite date” for equal pay in the public service. The EPCC backed that up by calling on its member societies to collect signatures for a petition to Parliament. It hoped for an ambitious 1 million signatures.

Little green buttons

Horton, a seasoned feminist campaigner whose mother had links with the suffragette movement, was a determined and capable organiser. She was well aware of the publicity value of the petition in reaching “the uninitiated and the unaware” and of the impact that marketing could have. Campaign merchandise included pencils emblazoned with equal pay slogans and “little green buttons” bearing the words ‘Equal pay for equal work’, available at sixpence each.

Progress on getting people to sign the petition was slow. By July 1953, Horton was writing to member societies to extend the deadline because “the coronation…made it virtually impossible to gain space in the press.” She offered advice on how to ensure the “widest publicity”, suggesting that, as well as house-to-house canvassing, “market stalls might be hired for a day; large shops might provide space for a table; and queues of all kinds might be canvassed.” She singled out cinema queues for the equal pay documentary ‘To Be a Woman’ by feminist film maker Jill Craigie as particularly fruitful.

Establishing working relationships with busy politicians required diplomacy and patience. Barbara Castle generously offered to book rooms in the Commons, but the demands of her job meant that confirmation of such bookings could be left to the last minute. As well as dealing with such challenges, Horton worked hard to maintain the cross-party consensus despite the inevitable frictions. On one occasion, Nancy Astor, the first woman to sit in the House of Commons, refused to attend an EPCC event because she felt so strongly about the issue that she feared she “might make a scene”.

Sherry will be provided!!

Early in 1954, Horton announced a deadline of 27 February, and asked campaigners to redouble their efforts to collect signatures. The committee had become aware of a rival petition put together by public service trade unions that was gaining momentum. Both petitions were scheduled for presentation in March, but by 11 February common ground was established and it was agreed to present them together on 9 March.

The pace of the campaign picked up during February: press releases were issued and meetings convened; former Conservative MP Thelma Cazalet Keir, who had tabled proposals during the war on equal pay for teachers, headed up an EPCC deputation to Chancellor Rab Butler demanding that the matter be dealt with in the Budget; and a rally was held in Hyde Park. Horton convened a sub-committee meeting to finalise arrangements, jokingly tempting Ward with the promise: “Sherry will be provided!!”

The schedule was meticulously planned. The four MPs arrived at the House of Commons in horse-drawn carriages, and posed for the press with placards and bundles of signed petitions. Ward presented the EPCC petition to the House of Commons, followed by Pannell, who presented the trade union petition. Then came questions on National Finance, with fierce exchanges on equal pay. “If the Chancellor still claims that Britain is too poor to pay its women civil servants equal pay,” scoffed Summerskill, “can he explain why it is that countries far poorer than Britain do not exploit their women civil servants as cheap labour?” Labour MP Douglas Houghton then presented a 10-minute rule Bill to establish the principle of equal pay. The focus on publicity paid off with enthusiastic press coverage. On 10 March, the Daily Worker reported: “If the pressure is increased…Labour MPs thought Mr Butler might be forced to concede the whole principle of equal pay.”

A gradual solution

On 6 April, Butler said in his Budget speech that “a gradual solution of this problem will prove to be the right one”. He offered to talk to public service pay negotiators. Campaigners were frustrated. On 8 April, addressing an audience of 500 women, Summerskill angrily picked up a jug of water and said “I feel like throwing this tonight.” Referring to an old anti-suffrage argument that women were not capable of fighting on the front line, she asked how Government could maintain “this prejudice against women when the H-bomb heralds an era when war will no longer be a man’s affair”. Ward called Butler’s mention of equal pay “a crumb” adding that “even that crumb is already disintegrating”.

On 9 April, the EPCC wrote to Butler deploring his failure to give a definite undertaking on the Government’s intention to establish reform. It completely rejected a gradual solution, as its members wanted full equal pay for equal work to be brought in quickly in the public services. At a meeting on 14 April, Horton said: “All will agree that the question of equal pay must be kept to the fore until the next budget or general election, whichever comes first.”

Equal pay for the civil service was completed on 1 January 1961 after a phased introduction from 1955. Full equal pay was achieved in 1970, when Castle piloted the Equal Pay Act through Parliament. The EPCC petition played a valuable role in the long road to legislative change with a media-savvy operation that transcended party politics. It kept the issue in the public eye, and is testament to the energy and determination of the campaigners, their daily frustrations, inspiration, persistence and political nous.

Hansard Writing Team, House of Commons

Sources

- Hansard, 2 August 1951, 16 May 1952, 11 February 1953 and 9 March and 6 April 1954

- Parliamentary Archives, File HC/CL/JO/4/6/13-14.

- Records of the Equal Pay Campaign Committee, Women’s Library, LSE. Files 6EPC/02 and 6EPC/03.

5 thoughts on “Women Demand Equal Pay!”

Comments are closed.