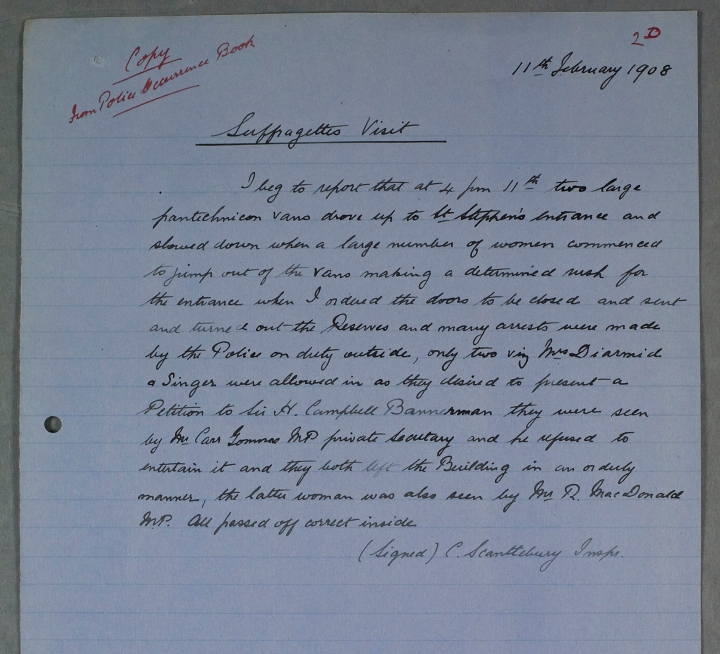

In February 1908, the ‘Pantechnicon Raid’ took place on the Houses of Parliament, when suffragettes were delivered to the front door in Pantechnicons, or furniture vans. To mark this 110 years on, we are pleased to publish this guest post by Dr Laura Schwartz on Charlotte Griffiths, one of the suffragettes involved.

Guest post by Dr Laura Schwartz

One hundred years ago this month, women were finally granted the parliamentary vote. Yet domestic servants, the most common type of woman worker in this period, remained disenfranchised. The new law removed the property qualification for men but retained it for women and because many servants ‘lived-in’ with their employers, even those over the new voting age of 30 did not qualify as ratepayers. The exclusion of servants from the 1918 Representation of the People Act points to the longer-standing difficulties that they faced in being accepted into the women’s suffrage movement. Although domestic servants were active at the grassroots, they rarely featured in formal suffrage propaganda and public spectacle and could not be easily incorporated into suffrage visions of modern and emancipated womanhood. Charlotte Griffiths, a domestic worker from Rochdale, was nevertheless an active advocate of votes for women and was even arrested for militant activity. Her story reveals the challenges experienced by servants who wished to lay claim to the emancipation also being sought by more middle-class women, and to assert a political voice independent from that of their employers.

Charlotte Griffiths was 50 years old when, on the evening of 11 February 1908, she joined hundreds of other suffragettes in a raid on the Houses of Parliament. Earlier in the day she had been participating in the Women’s Parliament, which had been organised by the WSPU to discuss the injustice of women’s continued disenfranchisement and the government’s repressive action towards militant suffrage campaigners. Initially, St Stephen’s Hall (part of the Houses of Parliament) was the target of a surprise attack by 21 suffragettes who arrived disguised inside a furniture removal van. Charlotte Griffiths joined the second wave of demonstrators attempting to enter the House in the evening, braving not only a ‘solid phalanx of police’, but also a ‘mob of boys’ who assaulted some of her party with ‘stones and sticks’.[1] Griffiths was one of the 50 arrested and tried at Bow Street Magistrates Court where, refusing to find two sureties of £20, she was served a six week prison sentence.[2] She spent only a week in Holloway Prison, however, accepting an offer of sureties to enable her to return home to nurse her ailing mother, paid for by John Albert Bright (Liberal MP for Oldham), and Gordon Harvey (Liberal MP for Rochdale).

Soon after the suffragettes’ raid on St Stephen’s, the General Committee of the National Liberal Federation debated the question of votes for women, during which Maurice Levy MP denounced a ‘band of women paid organisers … Bringing young girls from their employment, placing them on the streets of London amid horrible temptation’. He referred directly to Charlotte Griffiths’ arrest, claiming that John Albert Bright’s wife, Edith, ‘afraid to go out into the streets herself, allowed and induced’ her servant to ‘go and take part in the rowdyism’.[5] Charlotte Griffiths, however, refused to be portrayed as her mistress’ political puppet. The following week she wrote to the Manchester Guardian (the newspaper that had printed Levy’s slander) insisting that ‘I went entirely of my own free will, without any pressure or persuasion, but because I believed the cause was just and right, and that every woman who was able to do so should give her help.’[6] Rather than simply enacting the political enthusiasms of her employers, it is possible that, to the contrary, Griffiths might have helped spur this wing of the Bright family towards more active support for women’s suffrage. Certainly, it was her arrest that prompted John Albert to make his protest in the House of Commons, and also to address female enfranchisement in a speech the following week on the occasion of the election of a woman to Rochdale Town Council. His wife, Edith Bright, became president of the Rochdale branch of the North of England Society for Women’s Suffrage, and their daughter Hester Bright later became its secretary – but this branch was not founded until September 1908, a number of months after Charlotte Griffiths had served a week in Holloway prison.[7]

Charlotte Griffiths was one of a number of servants, low-status and underpaid working-class women, whose contribution to the struggle for the vote was rarely recognised, either at the time or in the histories that followed. It was often hard for domestic workers, who worked 16 hour days and were closely watched by their mistresses, to participate in public meetings and demonstrations. Other servants, with less sympathetic employers than Griffiths, lost their jobs when their political activity was discovered. Those who combined an assertion of their rights as women with demands for better pay and conditions as workers often faced snobbery and mistrust from more middle-class suffrage activists, who needed servants to keep their households going so that they were free to devote themselves to the Cause. Digitised newspapers and census records have now made it easier to recover the role played by women who rarely had the time to write diaries or memoirs which would have granted them a more definitive place in the historical record. These often frustratingly brief glimpses of the servants who struggled both for and sometimes within the suffrage movement, compel us not just to celebrate its achievements this centenary but also remain alert to its limitations and the complexities of its class politics. One legacy of servant-suffragettes like Charlotte Griffiths is to remind twenty-first century feminists that resistance to class and racial inequality must be a part of our ongoing struggle if we truly want liberation for all women.

Dr Laura Schwartz

Dr Laura Schwartz is Associate Professor of Modern British History at the University of Warwick.

[1] Manchester Guardian 12 February 1908, p.7.

[2] Rochdale Observer 19 February 1908, p.5; London Metropolitan Archive, ‘Register of the Court of Summary Jurisdiction at Westminster’, Part 1., 12 February 1908, PS/WES/A/01/052.

[3] The 1901 census records Charlotte Griffiths employed as ‘nurse domestic’ for John and Edith Bright in Hollington, Sussex. The 1911 census records her occupation as ‘nurse’ in the same household, now established at One Ash (the Bright family home, built by John Albert’s father), Rochdale. John Bright claimed that he had known her for 20 years, although he did not state in exactly what capacity, ‘The Imprisoned Woman Suffragists’, House of Commons debate, Hansard 13 Feb 1908, 184 cc284-8 http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1908/feb/13/the-imprisoned-woman-suffragists [accessed 30 August 2017].

[4] Rochdale Observer 19 February 1908, p.5; ‘The Imprisoned Woman Suffragists’, House of Commons debate, Hansard 13 Feb 1908, 184 cc284-8 http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1908/feb/13/the-imprisoned-woman-suffragists [accessed 30 August 2017]. The Hansard report reveals John Bright to have been rather mealy mouthed in his comments, describing Charlotte Griffiths as ‘a very worthy woman, however mistaken’, and the suffragettes in general as ‘high-minded’ ‘whatever they [the House] might think of their actions’.

[5] Manchester Guardian 22 February 1908, p. 10.

[6] Manchester Guardian 3 March 1908, p.5.

[7] Hester Bright became secretary in 1909/1910, Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain and Ireland: A Regional Survey (London: Routledge, 2008), p.11.