Guest post by Professor Barbara Goff

What can students of ancient Greece and Rome do to mark the centenary of some British women obtaining the vote? Surely ancient history had nothing to do with the struggles for suffrage? In fact, as an exhibition in the Classics Department of the University of Reading currently shows, the movement for women’s suffrage looked to ancient history for examples, inspiration, and even humour. The suffrage magazines Votes for Women and Common Cause regularly featured articles, creative writing, and cartoons that drew on the literature and history of ancient Greece and Rome. Suffrage agitators included prominent women, and many less well known, who had a classical education themselves or who were teachers of classics. Not only was Jane Harrison among this number, but also Janet Case, who played Athena in the 1885 Cambridge University production of Aeschylus’s The Eumenides (The Kindly Ones) and Margaret Nevinson, a classics teacher and wife of the campaigning journalist Henry Woodd Nevinson. Margaret Nevinson even wrote a book titled Ancient Suffragettes, which told the history of bold and rebellious women from the Bible, Greece and Rome.

A few examples will indicate this rich tradition of suffragists drawing on classical antiquity. John Stuart Mill presented the first petition for women’s suffrage to Parliament in 1867, and by 1873 Plato makes his first appearance in the Women’s Suffrage Journal, edited by Lydia Becker. He features as part of an argument calling for similar education for boys and girls. Plato is in fact one of the classical authors most regularly deployed by suffragists, along with Euripides. Because of his portrayal of assertive and dangerous women, like Medea, nineteenth-century critics often considered Euripides a misogynist, but suffragists reclaimed him for the women’s cause in a way that, from our vantage in the early 21st century, looks very familiar.

Sappho was another figure from antiquity who was very important to the suffrage cause. She is quite prominent in an event which the Actresses’ Franchise League and Writers’ Suffrage League together put on in 1909. This was the Pageant of Great Women, scripted by Cicely Hamilton and produced by Edith Craig, daughter of Ellen Terry. This was so popular that it was staged again in 1910, and toured to several locations. It was a pageant of women from various countries and historical periods, drawn together to defend Woman against her historical antagonist Man, in front of a figure of Justice. Sappho was the earliest woman represented, played by Miss Constance Collier, and there were also Hypatia and Boudicca from classical times. The Pageant was enthusiastically reviewed in the suffrage journals, but the Anti-Suffrage Review also saw it and concluded in November 1910 that the pageant ‘proved conclusively that the noble and unforgettable services of women to humanity in the past have suffered nothing from the want of the vote’.

The first edition of the Anti-Suffrage Review, in August 1910, contained a provocative article subtitled ‘If Sappho had never sung’; it concluded that although women are not intellectually inferior to men, ‘the sum total of human happiness, knowledge and achievement would have been almost unaffected if Sappho had never sung, if Joan of Arc had never fought, if Siddons had never played, and if George Eliot had never written’. The author thus takes the women who are pointed out as representative by the suffragettes, and diminishes their impact; he goes on to say that the true functions of womanhood, which are not very clearly defined but which probably include the birth and rearing of children, are more important to society, and are threatened by any measure that gives women the vote. A number of suffrage supporters wrote replies to this kind of argument. Elizabeth Robins, writer, actor and suffragist, published Ancilla’s Share in 1924, in which Sappho stands as the prime example of the way in which women can make outstanding cultural contributions, but have to pay the price of male antagonism. Typically for the time, Robins rejects the claims that Sappho was a woman who desired women, and suggests instead that her supreme poetic skill and talent incited the jealousy of men who then accused her of ‘the vice for which Lesbos sits through the centuries in the pillory of ill-repute’. Is there not a connection, she suggests, ‘between the fact that Lesbos was the nursing mother of intellectually free women, and man’s uneasiness in face of the intellectually free woman unless she was socially ostracised?’

The Romans are perhaps slightly less useful to the suffragists than the Greeks, but the historian Tacitus is frequently cited for his praise of the warrior-like women of the ancient Germans, and the British leader Boudicca also features in several different contexts, as well as in the Pageant of Great Women. To construct a tradition of warlike women was important when suffragists were combating the argument that physical force, the ability to take up arms against the enemy, was a necessary qualification for the vote. One of the suffragists’ own important arguments was that women should not remain unrepresented when they did have to pay taxes. A 1909 article on ‘Roman Suffragettes’ helps out with this. It begins ‘The Suffragette studies history’ and goes on to recount how Hortensia led the women of Rome in their refusal to contribute funds to the civil war. ‘It was Hortensia who enunciated on this occasion for the first time in history the principle of “no taxation without representation”. “Why should we pay taxes,” she cried, “when we have no part in the honours, the command, the statecraft, for which you contend against one another with such harmful results?”’ The author of the article does not need to state the obvious conclusion.

Greek and Roman history and literature also contributed less serious material. Laurence Housman, brother of the poet A . E. Housman, translated Aristophanes’ comic Lysistrata for performances by suffragists, who revelled in its portrayal of women ganging up on men to secure peace. Several writers in Votes for Women or Common Cause published parodies of Socratic dialogues, in which recalcitrant ‘antis’ discovered, just like Socrates’ interlocutors in Plato’s originals, that they could not defend their unexamined prejudices. My personal favourite is the fragment of an Antigone by Ethel Richardson. She writes that she was inspired to read Antigone by a hostile article in the Times which advised suffragists to remember the Greek playwrights. The author of that article had perhaps forgotten exactly how Greek dramas work – Antigone is the paradigm of a rebellious woman who is determined to bury her brother even though the king Creon has forbidden it. Richardson, however, adds a further twist. Don’t let the archaic translation detract from her clever replacement:

CREON: All Thebes sees this with other eyes than thine.

ANTIGONE: They see as I but bate their breath to thee.

CREON: And art thou not ashamed from them to differ?

ANTIGONE: To fight for one’s own sister is not shameful.

Sisterhood was powerful.

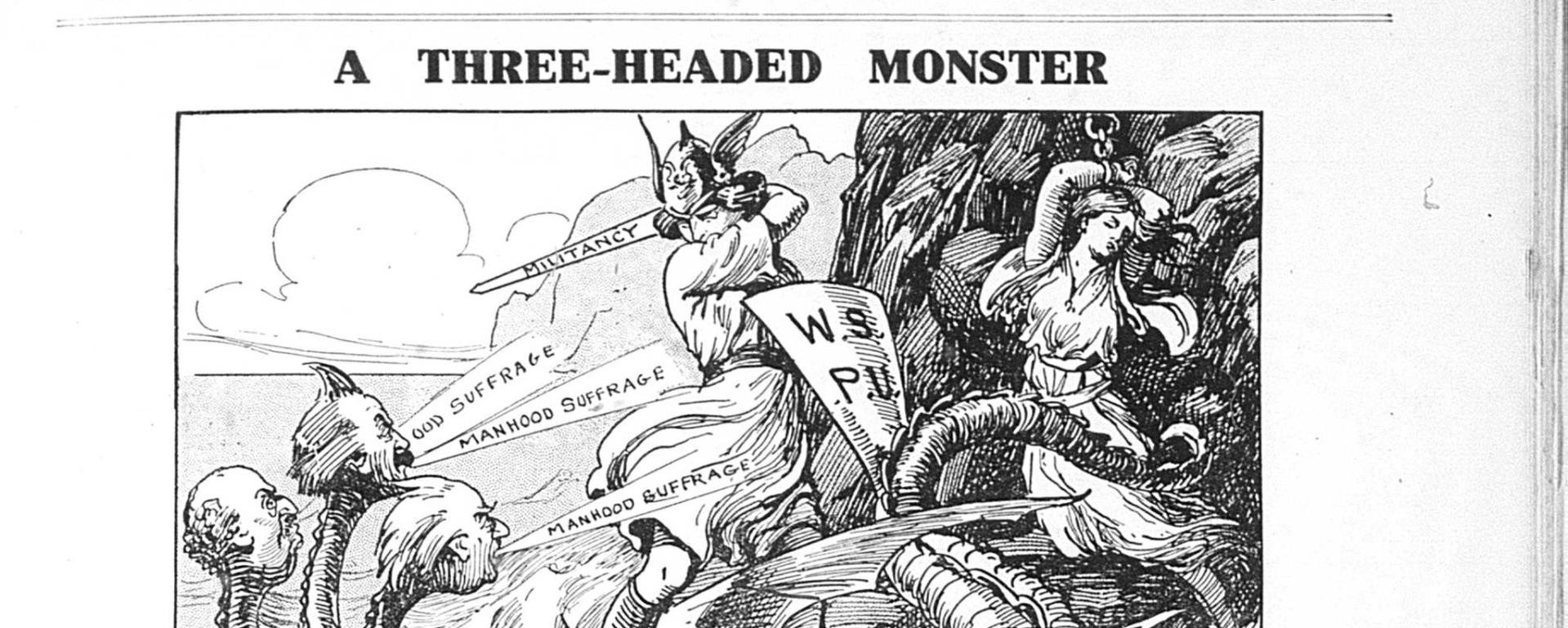

This image, another example of the more humorous side of the suffrage struggle, draws on classical mythology, as well as British legends like St George and the dragon, to show the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) defending a bound woman against the three-headed monster of contemporary male political leadership. The battling militant wields the authority of the classical world, even while challenging other powerful narratives that would have consigned her to a very different version of history.

!['A Three-headed Monster' by 'A Patriot' [Alfred Pearse]. Courtesy of the British Library Board.](https://ukvote100.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/barbara-goff-blog-image.png?w=720)

Barbara Goff is Professor of Classics at the University of Reading. Her exhibition is on the ground floor of the Edith Morley building on the Whiteknights campus of the University of Reading. Edith Morley was a suffragette and the first woman to be appointed a full professor at a university-level institution in the UK, in 1908 at University College, Reading, which became the University of Reading in 1926. The Edith Morley building is also home to the Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology, which has had women curators for most of its history.

One thought on “Ancient Suffragettes?”

Comments are closed.